La Ferme d’Hotte: Ciders with terroir

Although it is historically less respected than its neighbors to the north, the Aube has seen its winegrowing reputation surge over the past decade or so as an ascendent generation of producers coaxes increasingly expressive Champagnes from its Kimmeridgian soils. Less commonly known, however, is that the Aube is where some of the first apple ciders in France were produced—in an area known as the Pays d’Othe. This zone, situated 40 minutes northeast of Chablis, is a rolling, heavily forested countryside with soils of flint-rich clay over a Kimmeridgian-limestone bedrock. A bevy of indigenous apple varieties thrive here, yielding fruit of exceptionally high acidity and powerful minerality—a perfect backbone for cider.

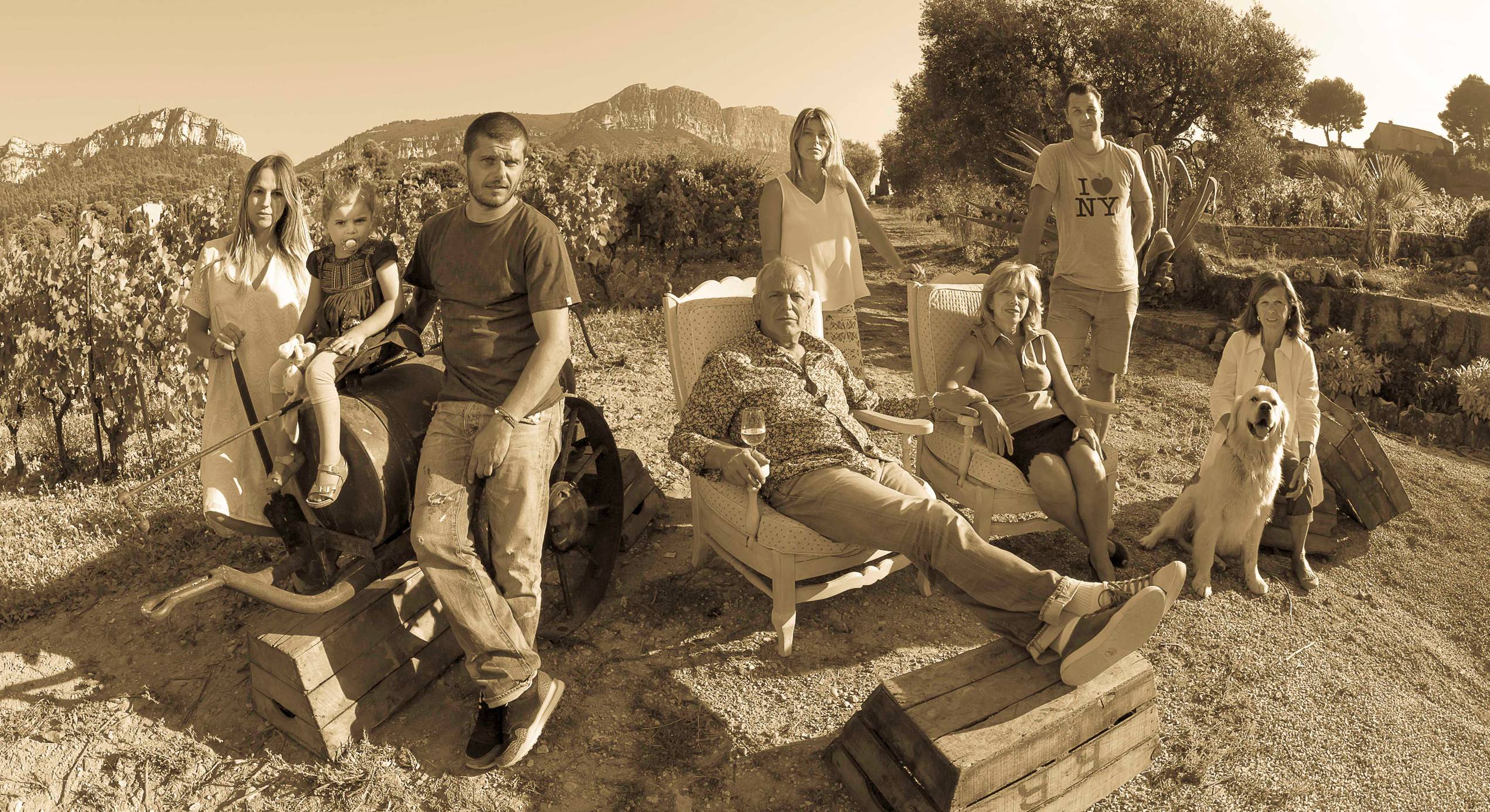

We were recently put in touch with a young man named Théo Hotte by a mutual acquaintance, who suspected his family’s ciders may be right up our alley. Théo is the fifth generation of Hotte to farm these fields around the town of Eaux-Puiseaux in the Pays d’Othe. The family’s old orchards were ripped up and planted to grains after World War Two, but Théo’s father began growing apples again in the 1990s, planting a bevy of varieties indigenous to the area. Following in his father’s footsteps, Théo works completely organically, and the farm is certified as such. It turns out our friend was right: this was indeed cider that spoke to our sensibilities: vivid and non-confected in its fruit character, bracing in its acidity, and evocatively rustic, with a commanding mineral presence on the palate.

Whether it’s for wine or cider, a cellar like La Ferme d’Hotte’s, with its rustic charm and simplicity, reassures the visitor: fashionable technology finds no purchase here. Apples are pressed within two hours of harvesting, and fermentations proceed in steel without any added yeasts. Pasteurization is never employed, and no sulfur is added at any point, including at bottling. Except for their elite cuvée “Boemius,” which is produced like Champagne, the second fermentation occurs when a small portion of unfermented and unfiltered juice is added to the cider at bottling, generating bubbles as the still-living yeasts in the juice devour the sugar. Remarkably, all of La Ferme d’Hotte’s ciders are kept two years before being put up for sale, and Théo enthuses about their age-worthiness, remarking that they continue to develop complexity and depth for well over a decade in bottle. Terroir is hardly the exclusive province of fermented grape juice, and it is thrilling to encounter ciders such as these which bear such an indelible sense of place.

More on La Ferme d’Hotte here.

Related