The dizzying Enfer d’Arvier perches above the ambling Dora Baltea River high in the Valle d’Aosta.

At Rosenthal Wine Merchant, the Alps have always been close to our heart. After all, the legendary Carema from Luigi Ferrando—situated at the grand entryway to the Valle d’Aosta—was the first wine Neal ever imported into the United States, back in early 1980. One of the most rewarding expansions of our work over the past decade and a half has taken place in this beautiful valley, first with the rock-solid Grosjean family, and soon after with the incredible Pavese family, working in the Valle d’Aosta’s highest-altitude pockets of viticulture.

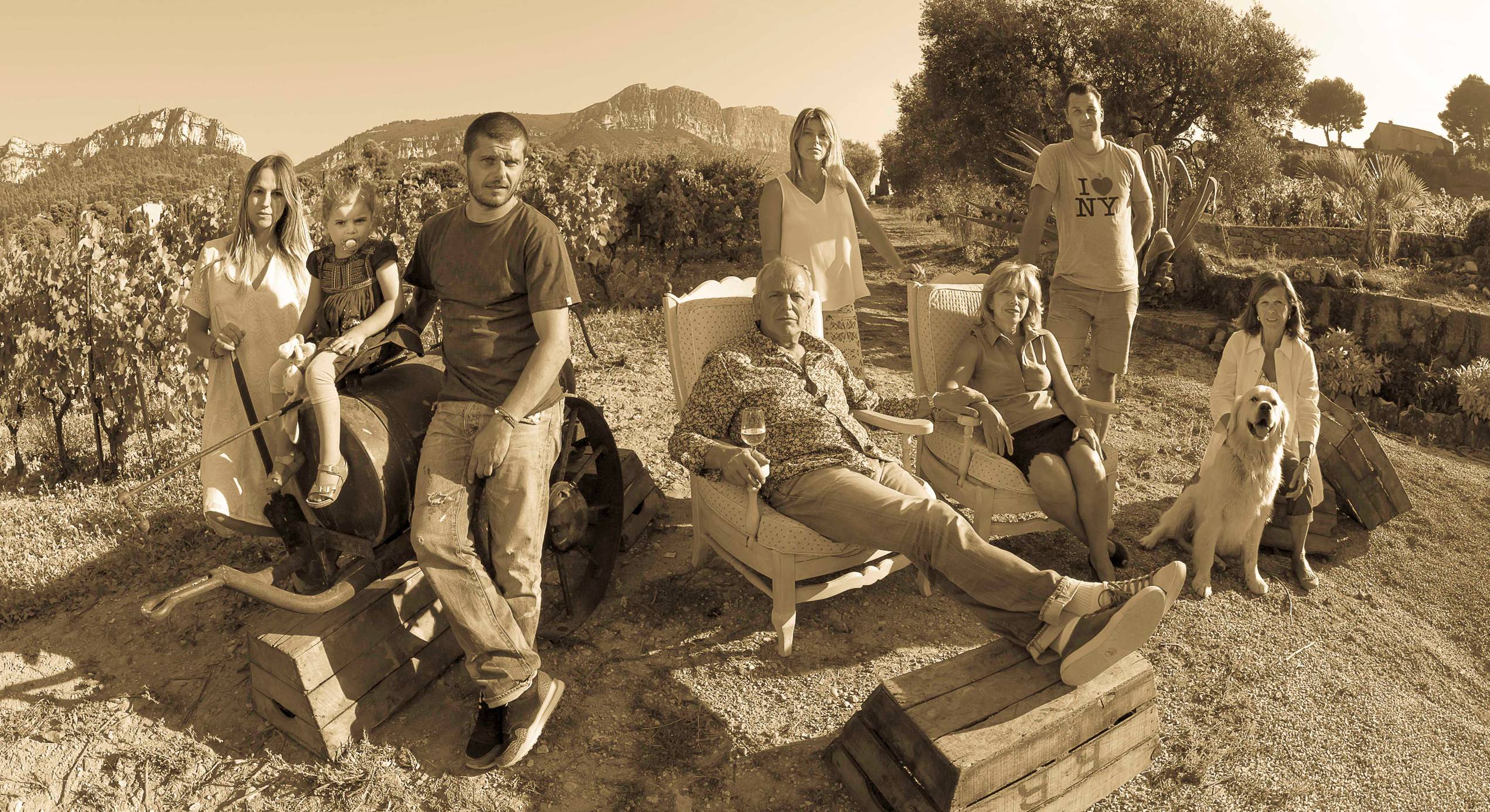

Around fifteen years ago, Ermes introduced us to the fast-talking, infectiously upbeat Danilo Thomain, a friend of his who lives just “downhill” in the hamlet of Arvier—home of the second-highest winegrowing zone in the valley. Encompassing a scant seven hectares, the Enfer d’Arvier is a splendorous amphitheater of steeply terraced vines flanked by the Dora Baltea River below. Given the miniscule vine holdings most landowners in the Valle d’Aosta possess, co-operatives still predominate in the region, and indeed the majority of the Enfer d’Arvier’s output is via the local co-op. With his two hectares in production—one of which he cleared and planted himself several years ago—Danilo stands as the only independent bottler of wine in this zone whose viticultural records date back to the 13th century.

Thomain’s Enfer d’Arvier is perhaps the most jubilant, boisterous red wine we import from the Valle d’Aosta. Produced entirely from the indigenous Petit Rouge, it’s a homemade wine in every sense of the word: these vertiginous terraces must be worked entirely manually; grapes are hand-harvested, carried just down the road to Danilo’s house, and the wine is made right there—fermented spontaneously, and aged in non-temperature-stabilized steel tanks in his basement two stories below the earth’s surface. The 2022 Enfer d’Arvier pours a typical saturated maroon in the glass, its inkiness hinting at the wine’s notable concentration of fruit. The nose is exuberant, brimming with black cherries, sun-drenched stones, tiny mountain flowers, and a tasteful touch of wild earthiness. The huge diurnal shifts between this zone’s scorching days—“Enfer d’Arvier,” after all, means “The Hell of Arvier”—and chilly nights expresses itself in a palate tango of rapier-like acidity and thick, luscious fruit.

More on Thomain here.

Related